|

| (French Hand Painted Unused Tapestry Cushion Cover Of The Knights Templar. "The Crusades to the Holy Land". ) |

The Crusades were a series of religious wars sanctioned by the Latin Church between the 11th and 16th centuries, especially the campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean with the aim of capturing Jerusalem from Islamic rule (War for the Holy Land). They were formally launched by Pope Urban II in the late 11th century to help the Byzantine Empire against the Seljuk Turks.

Pope Urban II, in one of history's most powerful speeches, initiated 200 years of the Crusades at the Council of Clermont, France on November 27, 1095 with this impassioned plea. In a rare public session in an open field, he urged the knights and noblemen to win back the Holy Land, to face their sins, and called upon those present to receive remission of sins and save their souls by becoming "Soldiers of Christ." Those who took the vow for the pilgrimage were to wear the sign of the cross (croix in French): and so evolved the word croisade or "Crusade." By the time his speech ended, the captivated audience began shouting "Deus le volt! - God wills it!" The expression became the battle-cry of the crusades.

Crusades were also fought for many other reasons such as to recapture Christian territory or defend Christians in non-Christian lands, resolve conflict among rival Roman Catholic groups, gain political or territorial advantage, or to combat paganism and heresy. The term crusade itself is modern, and has in more recent times been extended to include religiously motivated Christian military campaigns in the Late Middle Ages.

The crusades had a profound impact on Western civilisation: they reopened the Mediterranean to commerce and travel (enabling Genoa and Venice to flourish); consolidated the collective identity of the Latin Church under papal leadership; and were a wellspring for accounts of heroism, chivalry and piety. These tales consequently galvanised medieval romance, philosophy and literature. The crusades also reinforced the connection between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism.

Listed below are 9 crusades to the Holy Land between the 11th and 13th centuries.

Contents:

- First Crusade (1095–1099)

- Second Crusade (1147–1149)

- Third Crusade (1189–1192)

- Fourth Crusade (1202–1204)

- Fifth Crusade (1217–1221)

- Sixth Crusade (1228–1229)

- Seventh Crusade (1248–1254)

- Eighth Crusade (1270)

- Ninth Crusade (1271–1272)

- People's Crusade

- Children's Crusade

(See also The Northern Crusades)

(See also The Crusades Against Christians)

First Crusade (1095–1099)

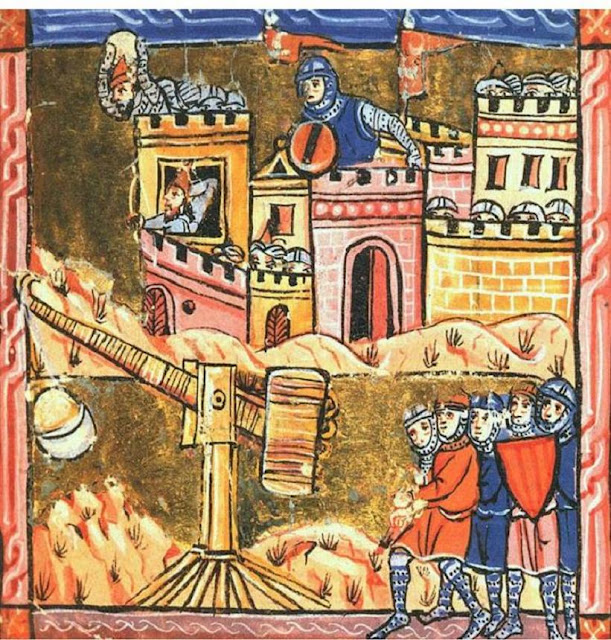

|

| (Miniature of the Siege of Jerusalem (1099) (14th century). Godfrey of Bouillon is using a siege tower to assault the walls.) |

On November 27, 1095, in Clermont, France, Pope Urban II called for a crusade to help the Byzantines and to free the city of Jerusalem. The official start date was set as August 15, 1096. Those armies that left before that time are considered part of the People's Crusade.

It started as a widespread pilgrimage in western Christendom and ended as a military expedition by Roman Catholic Europe to regain the Holy Land taken in the Muslim conquests of the Levant (632–661), ultimately resulting in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099.

As a result of the First Crusade, four primary crusader states were created: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli. On a popular level, the First Crusade unleashed a wave of impassioned, pious Catholic fury which was expressed in the massacres of Jews that accompanied the crusades and the violent treatment of the "schismatic" Orthodox Christians of the east.

Second Crusade (1147–1149)

|

| ("Raymond of Poitiers Welcoming Louis VII in Antioch" by Jean Colombe and Sebastien Marmerot (15th century), in Passages d’Outremer) |

The Second Crusade (1147–1149) was the second major crusade launched from Europe as Catholic ('Latin') holy war against Islam. The Second Crusade was started in response to the fall of the County of Edessa the previous year to the forces of Zengi. The county had been founded during the First Crusade (1096–1099) by King Baldwin of Boulogne in 1098. While it was the first Crusader state to be founded, it was also the first to fall.

The Second Crusade was announced by Pope Eugene III, and was the first of the crusades to be led by European kings, namely Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, with help from a number of other European nobles. The armies of the two kings marched separately across Europe. After crossing Byzantine territory into Anatolia, both armies were separately defeated by the Seljuk Turks. The main Western Christian source, Odo of Deuil, and Syriac Christian sources claim that the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos secretly hindered the crusaders' progress, particularly in Anatolia, where he is alleged to have deliberately ordered Turks to attack them. Louis and Conrad and the remnants of their armies reached Jerusalem and participated in 1148 in an ill-advised attack on Damascus. The crusade in the east was a failure for the crusaders and a great victory for the Muslims. It would ultimately have a key influence on the fall of Jerusalem and give rise to the Third Crusade at the end of the 12th century.

The only Christian success of the Second Crusade came to a combined force of 13,000 Flemish, Frisian, Norman, English, Scottish, and German crusaders in 1147. Travelling from England, by ship, to the Holy Land, the army stopped and helped the smaller (7,000) Portuguese army in the capture of Lisbon, expelling its Moorish occupants.

Third Crusade (1189–1192)

|

| (The Siege of Acre was the first major confrontation of the Third Crusade) |

The Third Crusade (1189–1192), also known as The Kings' Crusade, was an attempt by European leaders to reconquer the Holy Land from Saladin (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb). The campaign was largely successful, capturing the important cities of Acre and Jaffa, and reversing most of Saladin's conquests, but it failed to capture Jerusalem, the emotional and spiritual motivation of the Crusade.

After the failure of the Second Crusade, the Zengid dynasty controlled a unified Syria and engaged in a conflict with the Fatimid rulers of Egypt. The Egyptian and Syrian forces were ultimately unified under Saladin, who employed them to reduce the Christian states and recapture Jerusalem in 1187. Spurred by religious zeal, King Henry II of England and King Philip II of France (known as Philip Augustus) ended their conflict with each other to lead a new crusade. The death of Henry in 1189, however, meant the English contingent came under the command of his successor, King Richard I of England (known as Richard the Lionheart, in French Cœur de Lion). The elderly Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa also responded to the call to arms, leading a massive army across Anatolia, but he drowned in a river in Asia Minor on 10 June 1190 before reaching the Holy Land. His death caused tremendous grief among the German Crusaders, and most of his troops returned home.

After the Crusaders had driven the Muslims from Acre, Philip in company with Frederick's successor, Leopold V, Duke of Austria (known as Leopold the Virtuous), left the Holy Land in August 1191. On 2 September 1192, Richard and Saladin finalized a treaty granting Muslim control over Jerusalem but allowing unarmed Christian pilgrims and merchants to visit the city. Richard departed the Holy Land on 2 October. The successes of the Third Crusade allowed the Crusaders to maintain considerable states in Cyprus and on the Syrian coast. However, the failure to recapture Jerusalem would lead to the Fourth Crusade.

Fourth Crusade (1202–1204)

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Western European armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III, originally intended to conquer Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by means of an invasion through Egypt. Instead, a sequence of events culminated in the Crusaders sacking the city of Constantinople, the capital of the Christian-controlled Byzantine Empire.

In January 1203, en route to Jerusalem, the majority of the crusader leadership entered into an agreement with the Byzantine prince Alexios Angelos to divert to Constantinople and restore his deposed father as emperor. The intention of the crusaders was then to continue to the Holy Land with promised Byzantine financial and military assistance. On 23 June 1203 the main crusader fleet reached Constantinople. Smaller contingents continued to Acre.

In August 1203, following clashes outside Constantinople, Alexios Angelos was crowned co-Emperor (as Alexios IV Angelos) with crusader support. However, in January 1204, he was deposed by a popular uprising in Constantinople. The Western crusaders were no longer able to receive their promised payments, and when Alexios was murdered on 8 February 1204, the crusaders and Venetians decided on the outright conquest of Constantinople. In April 1204, they captured and brutally sacked the city, and set up a new Latin Empire as well as partitioning other Byzantine territories among themselves.

Byzantine resistance based in unconquered sections of the empire such as Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus ultimately recovered Constantinople in 1261.

The Fourth Crusade is considered to be one of the final acts in the Great Schism between the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church, and a key turning point in the decline of the Byzantine Empire and Christianity in the Near East.

Fifth Crusade (1217–1221)

|

| (Frisian crusaders confront the Tower of Damietta, Egypt, 1218. By Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen, circa 1625.) |

The Fifth Crusade (1213–1221) was an attempt by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering the powerful Ayyubid state in Egypt.

Pope Innocent III and his successor Pope Honorius III organized crusading armies led by King Andrew II of Hungary and Leopold VI, Duke of Austria, and an attack against Jerusalem ultimately left the city in Muslim hands. Later in 1218, a German army led by Oliver of Cologne, and a mixed army of Dutch, Flemish and Frisian soldiers led by William I, Count of Holland joined the crusade. In order to attack Damietta in Egypt, they allied in Anatolia with the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm which attacked the Ayyubids in Syria in an attempt to free the Crusaders from fighting on two fronts.

After occupying the port of Damietta, the Crusaders marched south towards Cairo in July 1221, but were turned back after their dwindling supplies led to a forced retreat. A nighttime attack by Sultan Al-Kamil resulted in a great number of crusader losses, and eventually in the surrender of the army. Al-Kamil agreed to an eight-year peace agreement with Europe.

Sixth Crusade (1228–1229)

|

| (Giovanni Villani's "Nuova Cronica" (14th century) depicting Frederick II's (left) and Al-Kamil's (right) meeting) |

The Sixth Crusade started in 1228 as an attempt to regain Jerusalem. It began seven years after the failure of the Fifth Crusade and involved very little actual fighting. The diplomatic maneuvering of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, resulted in the Kingdom of Jerusalem regaining some control over Jerusalem for much of the ensuing fifteen years (1229–39, 1241–44) as well as over other areas of the Holy Land.

The Sixth Crusade had many historical accomplishments. The most important being that the Papacy's power decline was now evident. Frederick also set the pace for the Seventh, Eighth and Ninth crusades as these were led by single kingdoms rather than an union of several ones, such as all the first crusades.

Jerusalem fell to the Turks only fifteen years later when the Turks successfully conquered it in 1244. However, the Christians had by then assimilated much of the Middle Eastern culture greatly influencing medieval life.

Seventh Crusade (1248–1254)

The Seventh Crusade was a crusade led by Louis IX of France from 1248 to 1254.

Despite a lack of enthusiasm from his closest barons and noblemen, and being seriously ill with malaria, Louis IX of France decided to launch a Seventh Crusade in December 1244 to reclaim Jerusalem, which had once again fallen into Muslim hands.

Just like the leaders of the Fifth Crusade, Louis IX succeeded to capture Damietta but he failed to capture Cairo. In addition, he was taken captive while trying to return to the port of Damietta. Approximately 800,000 bezants were paid in ransom for King Louis.

The Seventh Crusade has similarities with the Sixth Crusade in that both were conceived and carried out under the control of a monarch, rather than the Church. This highlights the declining power of the papacy, who had by now lost control of the crusading movement. As papal power faded, rulers were increasingly able to use the crusades as a tool of national policy. This shift in focus, however, is thought to have contributed in the part to the failure of so many of the crusades, including the seventh.

Eighth Crusade (1270)

The Eighth Crusade was a crusade launched by Louis IX of France against the city of Tunis in 1270. The Eighth Crusade is sometimes counted as the Seventh, if the Fifth and Sixth Crusades of Frederick II are counted as a single crusade. The Ninth Crusade is sometimes also counted as part of the Eighth. The crusade is considered a failure after Louis died shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia, with his disease-ridden army dispersing back to Europe shortly afterwards.

This crusade was called just 16 years after the Seventh Crusade. The Mamluks were now very powerful in the Middle East and were conquering the little territory left of the crusaders. Louis was persuaded by his brother, Charles of Anjou, to attack Tunis first in order to command the ports and make the conquest of Egypt, Louis' goal, easier. However, upon landing in Africa in 1270 much of the army became sick due to the water. Louis himself died on August 25, leaving Charles in full command of the army. Louis' last word was "Jerusalem".

The Eighth Crusade could be considered a partial success because Charles managed to receive trade rights with Tunis, even though diseases in the army prevented the city's assault. Charles allied with Prince Edward of England, who arrived in the interim. Even tough Charles didn't actively participate, Edward continued onto the Ninth Crusade.

Ninth Crusade (1271–1272)

|

| (Romantic portrayal of the "Last Crusader". "The Return of the Crusader", Karl Friedrich Lessing, 1835.) |

The Ninth Crusade, which is sometimes grouped with the Eighth Crusade, is commonly considered to be the last major medieval Crusade to the Holy Land. It took place in 1271–1272.

Louis IX of France's failure to capture Tunis in the Eighth Crusade led Henry III of England's son Edward to sail to Acre in what is known as the Ninth Crusade. The Ninth Crusade saw several impressive victories for Edward over Baibars. Ultimately the Crusade did not so much fail as withdraw, since Edward had pressing concerns at home and felt unable to resolve the internal conflicts within the remnant Outremer territories. It is arguable that the Crusading spirit was nearly "extinct," by this period as well. It also foreshadowed the imminent collapse of the last remaining crusader strongholds along the Mediterranean coast.

People's Crusade

|

| (Medieval illuminated manuscript showing Peter the Hermit's People's Crusade of 1096. Circa 1474. Miniature taken from Sebastien Mamerot's Overseas Passages.) |

The People's Crusade was the prelude to the First Crusade and lasted roughly six months from April to October 1096. It is also known as the Peasants' Crusade, Paupers' Crusade or the Popular Crusade as it was not part of the official Catholic Church-organised expeditions that came later. Led primarily by Peter the Hermit with forces of Walter Sans Avoir, the army was destroyed by the Seljuk forces of Kilij Arslan at Civetot, northwestern Anatolia.

Historically, there has been much debate over whether Peter was the real initiator of the Crusade as opposed to Pope Urban II. The expedition's independence has been used by some historians such as Hagenmeyer to prove this.

Children's Crusade

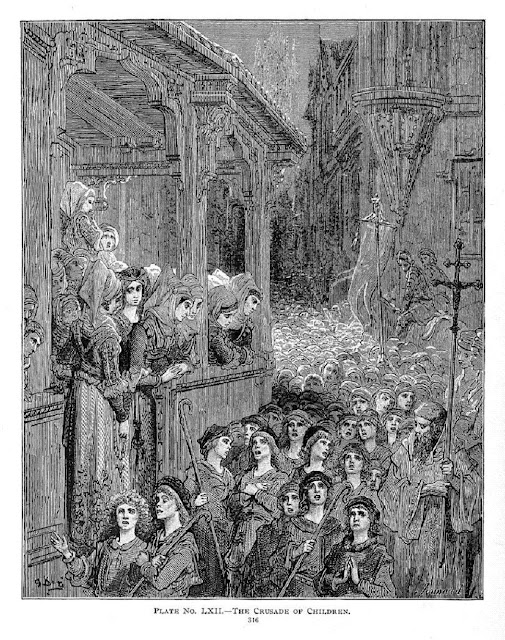

|

| (Depiction of the Children's Crusade by Gustave Doré. Date 1892) |

The Children's Crusade is the name given to a Crusade by European Christians to expel Muslims from the Holy Land said to have taken place in 1212. The traditional narrative is probably conflated from some factual and mythical notions of the period including visions by a French boy and a German boy, an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity, bands of children marching to Italy, and children being sold into slavery.

A study published in 1977 casts doubt on the existence of these events, and many historians came to believe that they were not (or not primarily) children but multiple bands of "wandering poor" in Germany and France, some of whom tried to reach the Holy Land and others of whom never intended to do so. Early versions of events, of which there are many variations told over the centuries, are largely apocryphal.