|

| (Courtmaster of the Teutonic Order (left) and Sword Brothers (right), 1870 Unknown Author) |

The success of the First Crusade inspired 12th-century popes such as Celestine III, Innocent III, Honorius III and Gregory IX to call for military campaigns with the aim of Christianization of the more remote regions of northern and northeastern Europe. The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades were religious wars primarily undertaken by the Christian military orders and kingdoms against the pagan Baltic, Finnic and Slavic peoples around the southern and eastern shores of the Baltic Sea. The crusades took place mostly in the 12th and 13th centuries and resulted in the conversion and baptism of indigenous peoples.

Most notable campaigns were Livonian and Prussian crusades. Some of these wars were called crusades during the Middle Ages, but others, including most of the Swedish ones, were first dubbed crusades by 19th-century romantic nationalist historians.

The Wendish Crusade of 1147 saw Saxons, Danes and Poles enforce Catholic control over the tribes of Mecklenburg and Lusatia, Polabian Slavs (or "Wends"). Celestine III called for a Crusade in 1193, but when Bishop Berthold of Hanover responded in 1198, he led a large army to defeat and his death. In response Innocent III issued a bull declaring a Crusade and Hartwig of Uthlede, Bishop of Bremen along with the Brothers of the Sword brought all of the north-east Baltic under Catholic control. Konrad of Masovia gave Chelmno to the Teutonic Knights in 1226 as a base for Crusade against the local Polish princes. The Livonian Knights were defeated by the Lithuanians, so Gregory IX merged the remainder of the order into the Teutonic Order as the Livonian Order. By the middle of the century, the Teutonic Knights completed their conquest of the Prussians before conquering and converting the Lithuanians in the subsequent decades. The order also came into conflict with the Eastern Orthodox Church in the form of the Pskov and Novgorod Republics. In 1240 the Orthodox Novgorod army defeated the Catholic Swedes in the Battle of the Neva, and, two years later, they defeated the Livonian Order itself in the Battle on the Ice.

Contents:

- Background

- Wendish Crusade (1147)

- Swedish Crusades (1150 • 1249 • 1293)

• First Swedish Crusade (1150)

• Second Swedish Crusade (1249)

• Third Swedish Crusade (1293) - Danish crusades (1191 • 1202)

• First Danish Crusade (1191)

• Second Danish Crusade (1202) - Livonian Crusade (1198–1290)

- Prussian Crusade (1217–1274)

- Lithuanian Crusade (1283–1410)

(See also The Crusades to the Holy Land)

(See also The Crusades Against Christians)

Background

|

| (A map of The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades (1115 – 1160)) |

The official starting point for the Northern Crusades was Pope Celestine III's call in 1195; but the Christian kingdoms of Scandinavia, Poland and the Holy Roman Empire had begun moving to subjugate their pagan neighbors even earlier. The non-Christian people who were objects of the campaigns at various dates included:

- the Polabian Wends, Sorbs, and Obotrites between the Elbe and Oder rivers (by the Saxons, Danes, and Poles, beginning with the Wendish Crusade in 1147)

- the peoples of (present-day) Finland in 1154 (Southwest Finland; disputed), 1191 (Danes), 1202 (Danes), 1249? (Tavastia) and 1293 (Karelia) (Swedish Crusades, although Christianization had started earlier),

- Livonians, Latgallians, Selonians, and Estonians (by the Germans and Danes, 1193–1227),

- Semigallians and Curonians (1219–1290),

- Old Prussians,

- Lithuanians and Samogitians (by the Germans, unsuccessfully, 1236–1316).

Armed conflict between the Baltic Finns, Balts and Slavs who dwelt by the Baltic shores and their Saxon and Danish neighbors to the north and south had been common for several centuries before the crusade. The previous battles had largely been caused by attempts to destroy castles and sea trade routes and gain economic advantage in the region, and the crusade basically continued this pattern of conflict, albeit now inspired and prescribed by the Pope and undertaken by Papal knights and armed monks.

Wendish Crusade (1147)

|

| (The Capture of the Wends; Wojciech Gerson (1831–1901), "Opłakane apostolstwo") |

The campaigns started with the 1147 Wendish Crusade (German: Wendenkreuzzug) against the Polabian Slavs (or "Wends") of what is now northern and eastern Germany. The crusade occurred parallel to the Second Crusade to the Holy Land, and continued irregularly until the 16th century.

By the early 12th century, the German archbishoprics of Bremen and Magdeburg sought the conversion to Christianity of neighboring pagan West Slavs through peaceful means. During the preparation of the Second Crusade to the Holy Land, however, a papal bull was issued supporting a crusade against these Slavs. The Slavic leader Niklot preemptively invaded Wagria in June 1147, leading to the march of the crusaders later that summer. They achieved an ostensible forced baptism of Slavs at Dobin but were repulsed from Demmin. Another crusading army marched on the already Christian city of Szczecin (Stettin), whereupon the crusaders dispersed upon arrival.

The Christian army, composed primarily of Saxons and Danes, forced tribute from the pagan Slavs and affirmed German control of Wagria and Polabia, but failed to convert the bulk of the population immediately.

Aftermath

The Wendish Crusade achieved mixed results. While the Saxons affirmed their possession of Wagria and Polabia, Niklot retained control of the Obodrite land east of Lübeck. The Saxons also received tribute from Niklot, enabled the colonization of the Bishopric of Havelberg, and freed some Danish prisoners. However, the disparate Christian leaders, mostly Canute and Sweyn, regarded their counterparts with suspicion and accused each other of sabotaging the campaign.

According to Bernard of Clairvaux, the goal of the crusade was to battle the pagan Slavs "until such a time as, by God's help, they shall either be converted or deleted". However, the crusade failed to achieve the conversion of most of the Wends. The Saxons achieved largely token conversions at Dobin, as the Slavs returned to their pagan beliefs once the Christian armies dispersed; Albert of Pomerania explained, "If they had come to strengthen the Christian faith ... they should have done so by preaching, not by arms".

The countryside of Mecklenburg and central Pomerania was plundered and depopulated with much bloodshed, especially by the troops of Henry the Lion. Of Henry's campaigns, Helmold of Bosau wrote that "there was no mention of Christianity, but only of money". The Slavic inhabitants also lost much of their methods of production, limiting their resistance in the future.

Swedish Crusades (1150 • 1249 • 1293)

The Swedish crusades were campaigns by Sweden against Finns, Tavastians, and Karelians during period from 1150 to 1293.

First Swedish Crusade (1150)

|

| (Eric IX of Sweden and bishop Henry en route to Finland. Late mediaeval depicion from Uppland.) |

The First Swedish Crusade was a possibly mythical military expedition around 1150 that has traditionally been seen as the first attempt of Sweden to convert pagan Finns to Christianity by force. According to the legend, the crusade was conducted by King Eric IX of Sweden. English bishop Henry of Uppsala accompanied him and remained in Finland. He was later killed at lake Köyliönjärvi by Lalli.

Academics debate whether this crusade actually took place. No archaeological data give any support for it, and no surviving written source describes Finland under Swedish rule before the end of the 1240s. Furthermore, the diocese and bishop of Finland are not listed among their Swedish counterparts before the 1250s. Also, the christianisation of the South-western part of Finland is known to have already started in 10th century, and in the 12th century, the area was probably almost entirely christian.

At the time, leading the leiðangr was the responsibility of the jarl. This gave rise to a theory that Eric conducted the expedition before he became king or pretender to the throne.[citation needed] Legends give no year for the expedition, and attempts to date it to an exact year in the 1150s are all much later speculations. All that is known about King Eric and Bishop Henry is that they most probably held important positions in Sweden some time in the mid-12th century.

The Swedish bishop normally involved in the eastern campaigns was the Bishop of Linköping, not the Bishop of Uppsala.

The mid-12th century was a very violent time in the northern Baltic sea, with Finnish tribes such as Tavastians and Karelians as well as Swedes in frequent conflicts with Novgorod and with each other. The First Novgorod Chronicle tells that in 1142 a Swedish "prince" and bishop accompanied by a fleet of 60 ships plundered just three Novgorodian merchant vessels somewhere "on the other side of the sea", obviously being after something more important.

Second Swedish Crusade (1249)

The Second Swedish Crusade was a Swedish military expedition to areas in present-day Finland by Birger Jarl in the 13th century. As a result of the crusade, the Swedish kingdom began to exert influence in western Finland.

Year of the crusade

According to Eric's Chronicle from ca. 1320-1340, the crusade took place between Birger Jarl getting elevated to the position of jarl in 1248 and the death of King Eric XI of Sweden in 1250. The so-called "Detmar Chronicle" of Lübeck from around 1340 confirms the expedition with a short note that Birger Jarl submitted Finland under Swedish rule. From other sources, Birger Jarl is known to have been absent from Sweden in winter 1249-50. Later on, the conquest of Finland was redated to the 1150s by the official Swedish legends, crediting the national saint King Eric for it. The point of time when the attack took place has been somewhat disputed. Attempts have been made to date the attack either to 1239 or to 1256. Neither date has received wide acceptance.

Aftermath

As an unexpected side effect, the expedition seems to have cost Birger the Swedish crown. As King Eric died in 1250 and Birger was still absent from Sweden, the rebellious Swedish lords selected Birger's under-aged son Valdemar as the new king instead of the powerful jarl himself.

From 1249 onwards, sources generally regard Finland proper and Tavastia as a part of Sweden. Diocese of Finland proper is first time listed among the Swedish dioceses in 1253. In the Novgorod First Chronicle Tavastians (yem) and Finns proper (sum) are mentioned on an expedition with Swedes (svei) in 1256. However, very little is known about the situation in Finland during the following decades. Reason for this is partly the fact that Western Finland was now ruled from Turku and most of the documentation remained there. As the Novgorod forces burned the city in 1318 during the Swedish-Novgorodian Wars, very little remained about what had happened in the previous century. The last Swedish Crusade to Finland took place in 1293 against Karelians.

Third Swedish Crusade (1293)

|

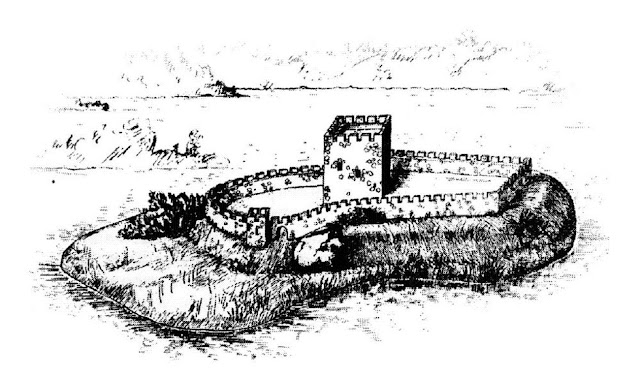

| (The first Vyborg Castle was founded during the so-called "Third Swedish Crusade" in 1293 by marshal Torkel Knutsson.) |

The Third Swedish Crusade to Finland was a Swedish military expedition against the pagan Karelians in 1293. It followed the First Crusade and the Second Crusade to Finland. As the result of the attack, Viborg Castle was established and western Karelia remained under Swedish rule for over 400 years. The name of the expedition is largely unhistorical, and it was a part of the Northern Crusades.

According to Eric Chronicles, the reason behind the expedition was pagan intrusions into Christian territories. Birger Magnusson's letter of 4 March 1295 states that the motive of the crusade was long-time banditry and looting in the Baltic Sea region by Karelians, and the fact that they had taken Swedes and other travellers as captives and then tortured them. Karelians had also been engaged in a destructive expedition to Sweden in 1257 which led Valdemar to request Pope Alexander IV to decleare a crusade against them, which he agreed.

According to Eric Chronicles, Swedes conquered 14 hundreds from the Karelians.

Danish crusades (1191 • 1202)

|

| (Anders Sunesen in the Battle of Lyndanisse 1219) |

The Danes are known to have made two crusades to Finland in 1191 and in 1202. The latter one was led by the Bishop of Lund Anders Sunesen with his brother.

First Danish Crusade (1191)

According to Danish annals, King Knud VI of Denmark sent an expedition to Finland in 1191 and “won it” [Danmarks middelalderlige annaler, ed. Erik Kroman (København: Selskabet for udgivelse af kilder til dansk historie, 1980), p. 18].

Second Danish Crusade (1202)

In 1202 another Danish army went to Finland under the leadership of Anders Sunesen, archbishop of Lund, and his brothers. They are also recorded as having led an expedition to Estonia in 1206. It is unclear whether these actions were undertaken in collaboration or competition with the Swedish crusades. The Sunesen brothers had close links with the Swedish king Sverker II Karlsson, who was married to their sister, and supported him against a rival claimant to the throne, Erik Knutsson. A more likely possibility is that the Danish activities in Finland were planned in conjunction with the Danish crusades to Estonia. In that case, it is probable that the Danes were not interested in the same areas as the Swedes, but rather, in the southern coastal regions along the Gulf of Finland.

However, Danish authority in this part of Finland must have collapsed together with other parts of the Danish crusading empire after 1223, when King Valdemar II Sejr was kidnapped by his rebellious vassal Count Henry of Schwerin.

Livonian Crusade (1198–1290)

|

| (A map of the Terra Mariana in 1260; Medieval Livonia) |

By the 12th century, the peoples inhabiting the lands now known as Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania formed a pagan wedge between increasingly powerful rival Christian states – the Orthodox Church to their east and the Catholic Church to their west. The difference in creeds was one of the reasons they had not yet been effectively converted. During a period of more than 150 years leading up to the arrival of German crusaders in the region, Estonia was attacked thirteen times by Russian principalities, and by Denmark and Sweden as well. Estonians for their part made raids upon Denmark and Sweden. There were peaceful attempts by some Catholics to convert the Estonians, starting with missions dispatched by Adalbert, Archbishop of Bremen in 1045-1072. However, these peaceful efforts seem to have had only limited success.

The Livonian Crusade refers to the conquest of the territory constituting modern Latvia and Estonia during the pope-sanctioned Northern Crusades: performed mostly by Germans from the Holy Roman Empire and Danes, it ended with the creation of the Terra Mariana and Duchy of Estonia. The lands on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea were the last corners of Europe to be Christianized.

On 2 February 1207, in the territories conquered, an ecclesiastical state called Terra Mariana was established as a principality of the Holy Roman Empire, and proclaimed by Pope Innocent III in 1215 as a subject of the Holy See. After the success of the crusade, the German- and Danish-occupied territory was divided into six feudal principalities by William of Modena.

Aftermath

In 1227 the Livonian Brothers of the Sword conquered all Danish territories in Northern Estonia. After the Battle of Saule the surviving members of the Brothers of the Sword merged into the Teutonic Order of Prussia in 1237 and became known as Livonian Order. On 7 June 1238, by the Treaty of Stensby, the Teutonic knights returned the Duchy of Estonia to Valdemar II, until in 1346, after St. George's Night Uprising, the lands were sold back to the order and became part of the Ordenstaat.

After the conquest, all of the remaining local population were ostensibly Christianized. In 1535, the first extant native language book was printed, a Lutheran catechism. The conquerors upheld military control through their network of castles throughout Estonia and Latvia.

The land was divided into six feudal principalities by Papal Legate William of Modena: Archbishopric of Riga, Bishopric of Courland, Bishopric of Dorpat, Bishopric of Ösel-Wiek, the lands ruled by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword and Dominum directum of King of Denmark, the Duchy of Estonia.

Prussian Crusade (1217–1274)

The Prussian Crusade was a series of 13th-century campaigns of Roman Catholic crusaders, primarily led by the Teutonic Knights, to Christianize the pagan Old Prussians. Invited after earlier unsuccessful expeditions against the Prussians by Polish princes, the Teutonic Knights began campaigning against the Balts in 1230. By the end of the century, having quelled several Prussian Uprisings, the Knights had established control over Prussia and administered the Prussians through their monastic state.

The Prussian populace retained many of their traditions and way of life, especially after the Treaty of Christburg protected the rights of converts. The Prussian uprisings led to the crusaders only applying these rights to the most powerful converts, however, and the pace of conversion slowed. After the Prussians were militarily defeated in the second half of the 13th century, they were gradually subjected to Christianization and cultural assimilation during the following centuries as part of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights. With the fall of Acre and Outremer and the securing of Prussia, the Order then turned its focus against Christian Pomerellia, which separated Prussia from imperial Pomerania, and against pagan Lithuania.

Campaigns of Konrad of Masovia

Konrad I, the Polish Duke of Masovia, unsuccessfully attempted to conquer pagan Prussia in crusades in 1219 and 1222. Taking the advice of the first Bishop of Prussia, Christian of Oliva, Konrad founded the crusading Order of Dobrzyń (or Dobrin) in 1220. However, this order was largely ineffective, and Konrad's campaigns against the Old Prussians were answered by incursions into the already captured territory of Culmerland (Chełmno Land). Subjected to constant Prussian counter-raids, Konrad wanted to stabilize the north of the Duchy of Masovia in this fight over border area of Chełmno Land. Masovia had only been conquered in the 10th century and native Prussians, Yotvingians, and Lithuanians were still living in the territory, where no settled borders existed. His military weakness led Konrad to invite the Teutonic Knights to Prussia.

The Northern Crusades provided a rationale for the growth and expansion of the Teutonic Order of German crusading knights which had been founded in Palestine at the end of the 12th century. Due to Muslim successes in the Holy Land, the Order sought new missions in Europe. Duke Konrad I of Masovia in west-central Poland appealed to the Knights to defend his borders and subdue the pagan Baltic Prussians in 1226. After the subjugation of the Prussians, the Teutonic Knights fought against the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Lithuanian Crusade (1283–1410)

|

| (Lithuanians fighting Teutonic Knights. Evolvent of relief. Original relief around first half of the 14th c.) |

The Lithuanian Crusade was a series of campaigns by the Teutonic Order and the Livonian Order, two crusading military orders, to convert the pagan Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Roman Catholicism. The Livonian Order settled in Riga in 1202 and the Teutonic Order arrived to Culmerland in 1230s. They first conquered other neighboring Baltic tribes – Curonians, Semigallians, Latgalians, Selonians, Old Prussians. The first raid against the Lithuanians and Samogitians was in 1208 and the Orders played a key role in Lithuanian politics, but they were not a direct and immediate threat until 1280s. By that time the Grand Duchy of Lithuanian was already an established state and could offer organized defense. Thus for the next hundred years the Knights organized annual destructive reise (raids) into the Samogitian and Lithuanian lands but without great success: border regions in Samogitia and Suvalkija became sparsely inhabited wilderness, but the Order gained very little territory.

The Grand Duchy finally converted to Christianity in 1386, when Grand Duke Jogaila accepted baptism from Poland before his wedding to reigning Queen Jadwiga and coronation as King of Poland. However, the baptism did not stop the crusade as the Order publicly challenged sincerity of the conversion at the Papal court. Lithuania, together with its new powerful ally Poland, defeated the Order in the decisive Battle of Grunwald in 1410, which is often cited as the end of the Lithuanian Crusade. The final peace was reached by the Treaty of Melno (1422).